On Monoculture & Brain Rot

"Who TF Did I Marry?!?" and "skibidi toilet rizz" may have been originated on the same platform, but have very different implications when brought up in conversation.

Last weekend, one of my friends invited me to hang out in Central Park with a group of women in their mid-20s. Sitting in the sunshine, eating chips and watermelon, and playing Catchphrase for nearly an hour, naturally, TikTok references naturally made their way into our conversations.

We briefly chatted about Hailey Bieber’s pregnancy and how several of us had seen the same influencer’s video recounting the time she saw Hailey hold her belly at Coachella. We also talked about the infamous “blanket couple” that’s recently been spotted around parks in NYC (if you know you know — I won’t elaborate).

As we chatted about these things, one girl said “I love monoculture. Because all of us here know exactly what I’m talking about.”

I was struck by this observation. I had never heard the word monoculture used to describe viral social media phenomena. The more I thought about it, the more I realized that it was the only word that aptly did so. Within moments, we all connected over a topic within seconds — and I couldn’t decide if I felt good or bad about it.

While social media-based monoculture creates an instant connection in real life, it also continues to plant our existence online. Even when we’re in person, we can only find things to talk about online. Some people might call “brain rot,” a symptom of being glued to the phone.

However, the two are mutually exclusive. In an age where people don’t just “go on the internet,” and instead consistently spend time online, monoculture thrives in the physical and digital worlds. Brain rot can’t move outside of digital spaces, no matter how hard people may try.

Monoculture in the context of TikTok

In 2019, tech journalist Kyle Chayka wrote an article in Vox about monoculture amid the nascent streaming wars and the rise of social media algorithms. Months after Game of Thrones finished its final season — a television show that many people thought would be the last moment of monoculture — people thought that social media subcultures and the fragmenting of entertainment across streaming platforms would put a halt to monoculture as we had known it.

It’s strange to think how Chayka’s ideas were propelled into full force a few months later during the pandemic. With television production slowed and the rapid rise of TikTok, people began to consume media across an array of different sources at a much higher cadence than before.

However, TikTok’s popularity introduced a new type of monoculture. Instead of watching the same television show or obsessing over an upcoming movie, people began to make Dalgona coffee (the viral whipped coffee), tie-dye clothes, and obsess over the Ratatouille musical. While the popularity of these trends originated from one application, they crossed over onto Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and more, as the collective internet obsessed over these trends. After all, the internet was the only way people could connect in a time of isolation.

In the years since 2020, the internet has been obsessed with popular television shows and movies, however, social media has helped democratize this experience. In February, Netflix’s “One Day” show captivated viewers alongside Reesa Teesa’s “Who TF Did I Marry?!?” series. In its first three weeks, One Day got 15.2 million views on the streaming service. On the other hand, Reesa Teesa earned over 400 million views on her 50-part saga in her first three weeks of posting.

While both of these extremely popular moments flourished on the internet, one of them cost $6.99 per month to watch (with ads!). Television shows can help create monoculture, but social media’s accessibility and ease of consumption allow these to become far more popular. After all, a lot of people don’t have the time to watch 8 hours of television. But they’ll easily make time to watch 8 hours of TikTok in a few days by watching when they wake up, on the train to work, on bathroom breaks, and before bed.

There’s also a greater collective assumption that people understand TikTok references better than a nod to a television show. With a multitude of streaming platforms and many popular television shows available to watch at once, the overarching popularity of a person or a trend on TikTok has a wider reach. After all, 62% of adults under 30 use the app.

It’s important to note that much of TikTok’s viral content is still siloed within the application. However, the popularity of the app has helped propel monoculture outside of it. One of the most memorable pop culture moments from Summer 2023 was the release of the long-awaited Barbie movie. People dressed up in pink to see the film in theaters, sang the songs from the film all summer, purchased plenty of Barbie brand items, and visited local dream house pop-ups. However, the real star of the show was the movie’s social media marketing, from selfie-generators to Barbie filters to the songs trending on TikTok. The monoculture created by the Barbie movie was perpetuated by social media, not simply created by it.

Too much screen time

Where monoculture celebrates the internet and how it brings people together so effortlessly, the term brain rot criticizes individuals who fail to distinguish between their internet and in-person interactions.

The word originated in 2023 to describe people who casually use internet jargon in their conversations so often that they lose touch with how to communicate normally. So much so, that whatever humorous thing they’re trying to say isn’t funny at all.

TikTok creator Joel Cave made a video in November titled “How to tell if someone has brain rot,” recounting a story from a college group project where one of the students would regularly reference TikTok audios and regurgitate trending phrases. Joel said it felt like a “Freudian slip,” and that this student should probably “get off of his phone and go outside.”

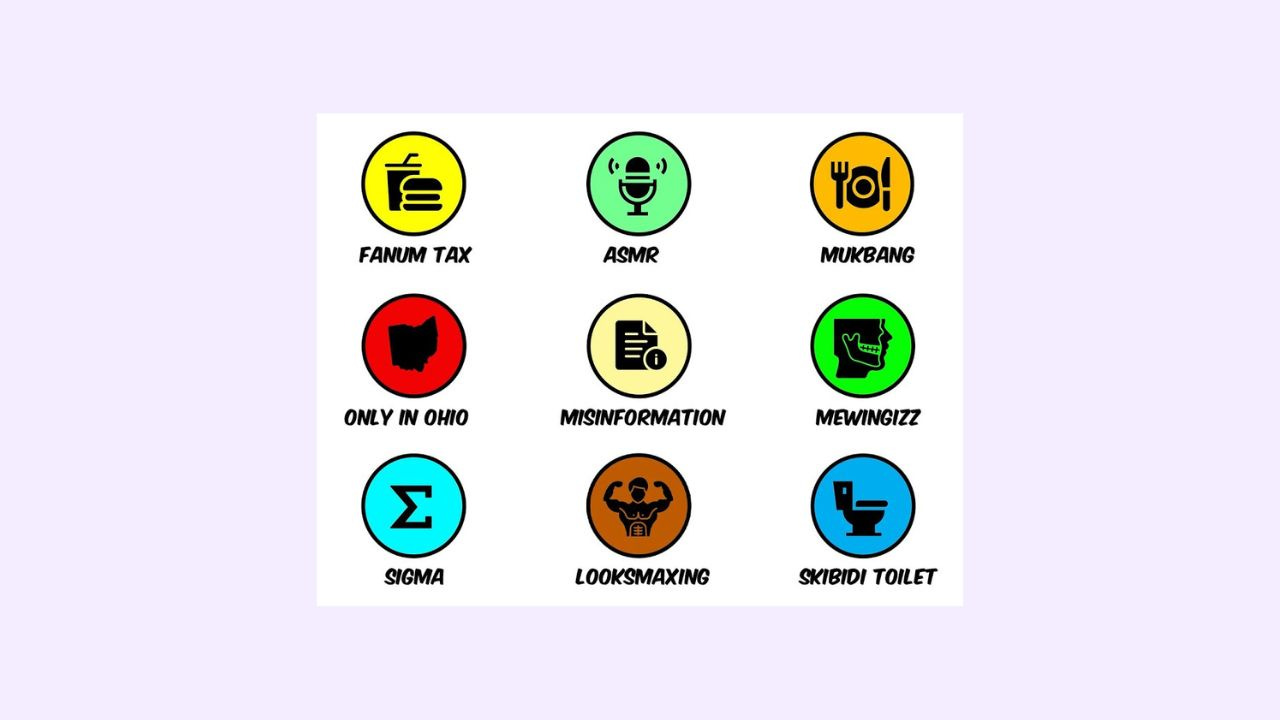

In 2023, the Oxford Dictionary named rizz the word of the year. Short for charisma, the word was popularized by streamer Kai Cenat (who was charged for inciting a riot in NYC’s Union Square last August.) The word has helped propel an entire Gen Z language that’s taken over TikTok. If you’ve seen a video that uses the words “rizzler,” “skibidi,” “ohio,” “gyatt,” and “fanum tax” in the same sentence, then you know how these words have been popularized across TikTok for months. If you haven’t seen the streaming references, perhaps you’ve heard someone ask if they’re “bunny pretty” or “2000s pretty,” or if they compare your “big back activities” to their “almond mom aesthetic,” or say “not me” before anything that comes out of their mouth.

While a lot of Gen Z understands these phrases or hears them from time to time in videos, there’s a collective understanding that they do not translate to the real world. They exist only in the context of TikTok, and trying to connect with someone about this off of the app is difficult to do. Saying “rizzler” or “big back activities” would imply to people that you’ve spent a lot of time on TikTok.

This is exactly where monoculture and brain rot differ: the former encourages community building around popular media, while the latter discourages adopting TikTok phrases in daily conversation.

Maybe it’s a generational thing?

There’s an argument that people who criticize others for having brain rot and speaking are simply too old to understand. After all, many of the articles that define these terms or explore these origins claim that they are popular among Gen Alpha. As an older Gen Z myself, it’s not something I would be able to casually say in a conversation, but for the younger generation, it may become monoculture down the line.

Gen Alpha is defined by their true digitally-native experience: growing up with iPads, watching their parents post their baby pictures on Instagram, and getting social media accounts at a very young age. Specific words they use day to day, stemming from their experiences on TikTok, may become a regular part of their vocabulary in a few years. They may not have any issue using words they learned on social media in person because they truly may not know better.