TikTok May Die Soon — But Authenticity on the App Is Long Gone

If the one thing that sets TikTok apart from other social media apps no longer exists, then what does the impending ban change?

It’s January 2025. And for US-based TikTok users like myself, we might only have one week left before the app gets banned, removed from app stores, and ceases to update to a point it’s no longer usable on an iPhone.

Content creators and their audiences are upset with the Supreme Court’s fight to get rid of the app. But if what originally drew users to TikTok was its celebration of authentic content — peeling back the layers of overly staged and edited Instagram photos or YouTube videos — that’s long gone. The nail in the coffin is the process of trends that prompt vulnerability being spun into memeified content — punishing creators who authentically interact with their audiences.

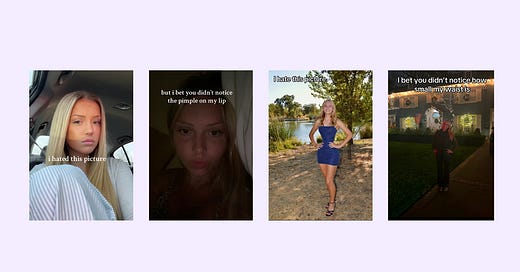

A couple of weeks ago, several young female creators began posting slideshow-style TikToks of themselves in an effort to empower self-love. As seen in one young woman’s video, she began her slideshow by with a selfie and overlayed text reading “I hated this picture.” The next slide says “but bet you didn’t notice the pimple on my lip.” She continues the slideshow continues with more photos of herself she “hated,” and then points out small components of the previous photo that viewers likely didn’t notice. She ends the video with a slide stating “moral of the story is your ur biggest critic and nobody notices what you see, so let go of the imperfections.”

It’s a powerful message, especially to a young female audience. And, it’s mostly true that no one notices the insecurities you hold most deeply about yourself. While many viewers commented “the fact I didn’t notice any,” or “I noticed that you are beautiful,” others commented negatively, saying things like “I noticed all of these things immediately,” or “omg u pmo,” which I recently learned, means “piss me off.”

Trolls always find a way to leave nasty comments, and often times, can collectively influence how other creators should proceed in adapting this trend. After many other women posted vulnerable videos calling out features that make them self-conscious, the trend began to devolve into young women posting heavily-edited photos of themselves to call attention to fake insecurities. One young female creator posted a slideshow TikTok with the first photo’s text reading “I hate this picture.” In the photo, her waist was visibly FaceTuned to look abnormally small, and the next slide read “bet you didn’t notice how small my waist is.” The following photo read “I hate this picture,” with her teeth colored-in yellow, and the next slide read “I bet you didn’t notice my yellow teeth.” Users left comments like “I bet y’all didn’t notice this video was a joke,” or “Thank you for making me laugh I needed this.”

Some users commented “I noticed them all” — and whether or not they were serious, the memefied version of this trend builds a shield of armor for the creator to withstand any hate. Sure, it’s entertaining — but spoofing on a trend that praises vulnerability makes posting authentically appear a selfish, narcissistic act that is important to avoid in order to be successful on the app.

I first noticed this pattern about a year ago. In early 2024, many young female creators caught onto a trend where they’d post a slideshow of themselves with the first photo stating “Social media is fake. Here are some things I’ve been struggling with.” They’d go on to list their struggles in the following slides. From body dysmorphia, to acne, to anxiety and depression, creators large and small got very honest with their audiences about their deepest struggles.

It didn’t take long for creators to make the trend silly, though. People started posting superficial, obscure struggles in an attempt to memeify the trend. Some creators posted “I cannot stop thinking about sweet treats,” or “I hate home-cooked food,” or “I am fully convinced I can beat up any man I don’t like.” One creator even posted “Don’t worry about what I got going on” — which I wrote about in the context of the abundant oversharing problem on TikTok for the first issue of The Influenced.

If authenticity was the number one thing that brought users to TikTok in the first place, then I struggle to understand why they’re upset about a ban. Creators’ attempts to be vulnerable, and potentially overshare for the sake of connecting with their audience, is met with an abundance of trolls. Haters aren’t new, but the way that any raw trend quickly devolves into humorous content harms the creators who took the leap of faith to post something a bit scary, and the viewers who may have felt deeply connected to this content.

So again, if what made TikTok ‘TikTok’ is long gone, I don’t know why people care so much about its departure from the US.